Scale it up and it’s revolution; scale it down and it’s individual non-cooperation that may be seen as nothing more than obstinacy or malingering or not seen at all. What we call protest identifies one aspect of popular power and resistance, a force so woven into history and everyday life that you miss a lot of its impact if you focus only on groups of people taking stands in public places. But people taking such stands have changed the world over and over, toppled regimes, won rights, terrified tyrants, stopped pipelines and deforestation and dams. They go far further back than the Peterloo protests and massacre 200 years ago, to the great revolutions of France and then of Haiti against France and back before that to peasant uprisings and indigenous resistance in Africa and the Americas to colonisation and enslavement and to countless acts of resistance on all scales that were never recorded.

They will go far forward from this moment. And at this moment, with organisations addressing the climate crisis, reinvigorated feminism in many parts of the world, antiracist and human rights campaigns focused on specific groups and issues, protest is a force running through everything – and running against a lot of things, since this is also an age of authoritarianism and a consolidation of wealth among a global superelite.

Right now, for example, Florida’s Coalition of Immokalee Workers is forming another alliance with students to pursue rights for farmworkers by targeting nationwide US burger chain Wendy’s. They can stand as one of the great examples of the power of the supposedly powerless, which could be more fruitfully thought of as exercisers of other kinds of power than institutional, military, or financial power, the kind less seldom recognised, cultivated, studied or valued. This alliance of labour organisers and immigrant farm workers from the Caribbean, Central America and Mexico began co-ordinating human rights and workers’ rights campaigns almost two decades ago, from a base in the tomato-growing region around the town of Immokalee in Florida. It would be easy to call immigrant farm workers powerless, and indeed modern-day slavery was one of the issues they addressed.

But they understood the nature of power: to get a living wage, they needed to get a few cents more per box of tomatoes, and pressuring the farmers wasn’t going to work, so they went after the buyers, the big supermarkets and fast-food chains, targeting one at a time, building coalitions, media campaigns, holding marches and other public events. And winning. They conquered Taco Bell in 2005. Then McDonald’s. Then Burger King, Whole Foods Market, and Subway by 2008, and they kept going. They fought modern-day slavery, sent the enslaving farmers to jail and established workplace standards that recently expanded to address the epidemic of sexual harassment and abuse in the fields. “Todos somos líderes” (We are all leaders) is one of their sayings, insisting that power is everywhere and everyone can exercise it as they do.

The people who first and last resist slavery, then and now, are the enslaved, and the history of 18th-century England and Scotland includes lawsuits and other tactics to free individual slaves. Olaudah Equiano, who was kidnapped from his Igbo village in what is now south-eastern Nigeria and sold into slavery, purchased his own freedom and became an anti-slavery activist in England. In 1789 he published a widely read autobiography that deepened and broadened knowledge of the brutalities of slavery. Part of the danger of imagining change as a process forced by violence and brute power is that it overlooks the great power of nonviolent uprisings and those other moments when individuals become a civil society on its feet.

It also ignores how the most important battle is often in the collective imagination, and it is won in part by books, ideas, songs, speeches, even new words and frameworks for old evils. The second US president, John Adams, said the American Revolution took place “in the minds and hearts of the people” before hostilities commenced. What makes something long tolerated intolerable, what makes people not directly affected care, what sways public opinion, what tips the balance, what makes politicians recognise that the dangers of not acting have come to outweigh those of acting? Another thing to remember about the great public moments, whether it’s the uprisings against the World Trade Organization in Seattle and elsewhere in 1999, or the global protest against the Iraq war in 2003, or the 2017 women’s marches in hundreds of places across the globe, is that they are not the planting but the harvest of a change in public imagination.

People cared; something made them care; people were ready to act; something made them ready; people joined; someone or many someones issued the call and orchestrated the action. One metaphor that has worked for me is: the mushrooms that spring up after rain are only the fruiting body of a far larger underground fungus we do not see; the rain causes the mushrooms to rise out of the earth, but the fungus was alive and well (and invisible) beforehand; the rain can be an event. Think of Donald Trump’s immigration ban on seven predominantly Muslim countries that caused Americans to go to airports all over the country in January 2017, or how the lack of adequate action on the climate crisis prompted Extinction Rebellion to take over key sites in London in April. And then these public actions often have consequences of their own; that the UK parliament declared a climate emergency at the beginning of last month is undoubtedly in part a response to this action, but of course the official powers – let’s call them the aboveground powers – do not like to acknowledge the underground powers, and so they generally dismiss, ignore, or demonise them. But we do not have to. In these great collective moments people showed up because they cared; when they showed up they often found a new sense of solidarity and power, which generated yet more possibilities.

The seeds of a great public anti-slavery campaign in the western world were planted on 22 May 1787. That day, a group of 12 Quaker men gathered in a printing shop in London to launch a campaign that, as Adam Hochschild relates in his magnificent book Bury the Chains, would take almost 50 years to succeed, and only one of them would survive to see the end of, a campaign to end slavery throughout the British empire. Among the tactics the movement deployed, as the years passed, were a sugar boycott, the now famous engraving of how Africans were packed into the hulls of slave ships, letter writing and lobbying parliament, engaging the public in the campaign. These are now common tactics for social change. In 1807, buying and selling slaves became illegal across the empire; owning slaves became illegal by a process beginning in 1833. It was a process more considerate of slave owners than slaves, compensating the former rather than the latter, but it freed slaves and outlawed slavery.

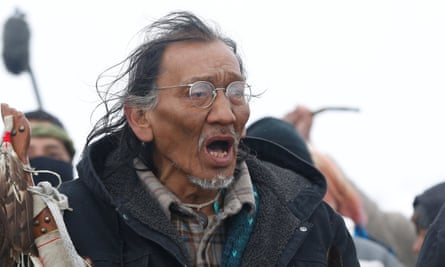

Liberation is contagious, as an idea and as a process. One of the most extraordinary chains of events of the 19th century was the response of American women active in the US abolitionist movement, who were excluded from even being seated, let alone speaking, at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, in June 1840. It prompted women already involved in trying to end slavery to begin looking at their own lack of rights, freedoms and equalities. The result was the suffrage movement, which made the antislavery movement look speedy; it took 80 years to ratify the 19th amendment to the US constitution, declaring no one would be denied the right to vote “on account of sex” (and we’re still fighting in the US for the right to vote regardless of race). It prompted suffrage movements in other countries around the world. I don’t know exactly how the black civil rights movement triggered the other racial justice movements around the US for Latinx, Asian American and Native American rights, but I know that 50 years ago the Native American occupation of Alcatraz Island had a huge impact. As with the Standing Rock protests against the Dakota Access pipeline three years ago, the campaign went far beyond its boundaries and official goals.

I described these great public actions as harvests of the seeds planted before them; the ripe crop generates more seeds. The great gathering of resistance at Standing Rock inspired Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to run for office, and her success and subsequent actions have been extraordinary in their dedication to tackling the climate crisis, notably with the Green New Deal. Standing Rock, I have been told, inculcated pride and hope and a sense of power, as well as bringing about new alliances and healing old conflicts, for many Native American participants. It also raised awareness of indigenous rights and land issues for a lot of non-native people. Like the long campaign against the proposed Keystone XL oil pipeline from Alberta, Canada, to Nebraska in the midwest, it served as an education for people around the continent and beyond about the role of pipelines in making fossil fuel extraction profitable, the dangers and impacts and politics.

There is nothing more direct than an encampment of several hundred people or a march of tens of thousands, but that does not mean the consequences will be direct, or that only the direct and measurable ones matter. Every action shifts the world’s balance, sometimes those shifts will never be noted or will have their impact long after or far away. At Peterloo, unarmed people were massacred by armed cavalry; it’s easy to portray this as a defeat, but it is said to have shifted the balance in such a way that the issue of universal male suffrage became urgent and led 13 years later to the Reform Act of 1832. This newspaper was established in the aftermath of Peterloo, to “warmly advocate the cause of Reform”, and so this publication is an unforeseen consequence of that massacre. Violence did not win, if it meant doing more than killing, dispersing and terrifying protesters; it did not kill an idea of justice and it may have hastened its advancement. At Standing Rock, hired thugs and government agents attacked protesters, often brutally, but they did not stop the beliefs, the hopes, the ideas, or the awareness. Violence can intimidate more than it can convert. “You can cut all the flowers, but you can’t stop the spring,” Pablo Neruda once wrote.

That was a beautiful expression that perhaps the climate emergency has sabotaged as a literal truth. Spring this year came as devastating floods across Mozambique and the central US, as freak late snowstorms, as record heat in the Arctic, as cherry blossoms blooming early in Japan. We didn’t stop the spring, but we warped it. The future of the Earth and all living things on it now depends on whether we do enough in response to the climate crisis to limit its impact by radically transforming our energy production and consumption, our agriculture and forestry, our priorities and perceptions.

This too has been led largely from underneath, by grassroots climate activists from the Philippines to Alaska, and they have accomplished astonishing things in the past dozen years, shutting down coal plants, stopping coal and natural gas terminals, pipelines, fracking (with outright bans in some US states, notably New York, and some countries, including France, Germany and Ireland). A technological revolution in wind and solar power will allow us to enter a post-fossil fuel age, but to do that means countering the great powers of the fossil fuel corporations, profiteers and the governments that serve them better than their citizens. This is a conflict that pits the young, some of whom are likely to live to see the 22nd century, against the old; it pits the poor and the people of the global south, who are feeling the impact most now, against the rich and the people of the north, who are largely responsible for the climate crisis.

It has been, and will be, a conflict of the apparently powerless against the apparently powerful. We will need to remember our past victories, the powers of protest, but also of art, of transformations of imagination, of widespread non-cooperation. It is more than a conflict, though. The response to the climate crisis must be a transformation of everything from transportation systems to imaginations. Some already recognise an Earth in which everything is beautifully and terrifyingly interconnected, in which the coal we burn now, or don’t, has everything to do with the climate of the future, in which forests are the most elegant technology to sequester carbon – and in which the young now lead us.

Greta Thunberg is the most famous of the new generation of climate activists, but the youth plaintiffs in the Oregon-based youth climate lawsuit and the young leaders of the Sunrise Movement and Extinction Rebellion count. I name them because they are visible to me in western America, but I know that extraordinary young people are at work in every part of the world – including 25 activists, ranging in age from seven to 25, who have just won a lawsuit in Colombia to stop Amazon deforestation, and the poet Aka Niviana who has raised awareness of the accelerating ice melt across Greenland. And I know that the power they have, and we have, could be adequate to this greatest of crises if we can understand it, imagine a different world, and make it happen with the tools we have always had but not always recognised. If …

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion